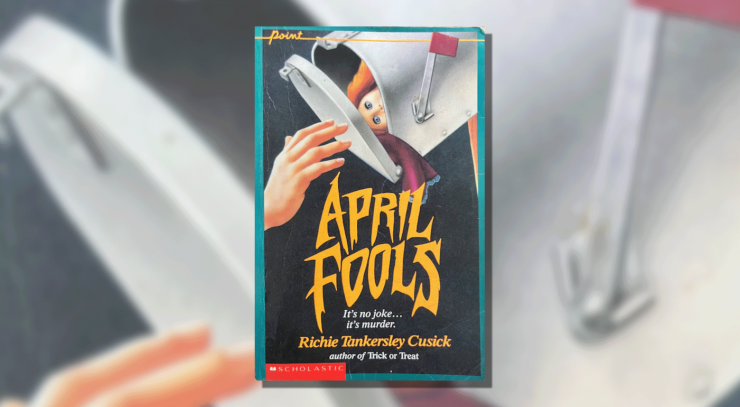

April Fools’ Day is a day of pranks, tricks, and gotchas, but not all pranks are created equal. While some of these jokes may be all in good fun, others can be mean-spirited and even downright dangerous. This is definitely the case with Richie Tankersley Cusick’s April Fools (1990), when the aftermath of an April Fools’ Day party gone wrong haunts a group of teenagers and nearly cost them their lives.

High schoolers Belinda, Hildy, and Frank go to an out-of-town April Fools Day party. The party is about two hours away from their hometown, but it’s being thrown by some of Frank’s college friends and is going to be pretty wild, with plenty of beer, so they figure it’s worth the trek. Given this set up, it’s not hard to imagine all the ways things can go wrong, and Cusick immediately validates readers’ concerns in the book’s prologue, opening with “Later, when Belinda thought about that horrible night, she could think of a hundred ‘if only’s’ that might have made things turn out differently. If only we hadn’t gone to that party … If only we hadn’t tried to drive there and back again. If only Frank hadn’t drunk all those beers … If only it hadn’t been April Fools’ Day” (1, emphasis original). Frank drunkenly declares himself “King of Fools” (2) and even though he’s almost too drunk to walk, he tries to insist on driving the trio home. Hildy is able to wrest the keys from Frank, doing her best to get them home through a thunderstorm on dark and unfamiliar roads, which is made even more challenging by Frank reaching across from the passenger seat to try and grab the steering wheel and step on the gas pedal.

As if this doesn’t make for a nightmarish enough road trip, another car pulls up behind them, honking and trying to pass on the sharply curving roads, which quickly becomes a legitimately dangerous interaction, as the drivers nearly run one another off the road and “Frank’s foot hit the gas pedal, lurching them forward, right into the other car’s bumper” (3). Tires are squealing, Frank is laughing hysterically, the girls are screaming for him to stop, and suddenly … everything goes quiet and the car that was in front of them has disappeared. The silence doesn’t hold for long though and a few seconds later, Belinda hears “the terrible, unbelievable noise not so far away—the crash going on and on through the dark and the thunder, and the crunching and twisting of metal, and the helpless, panicky screams—” (4). Hildy stops the car and Belinda runs down the embankment to try to help, horrified to see someone trapped inside the burning car and screaming to be rescued. Belinda’s friends pull her away and out of range of the car before it explodes, shove her back in the car, and flee the scene, but not before Belinda sees someone silently watching them and looking over the aftermath of the accident.

Two weeks later, Belinda is still haunted by what they did and by the screams of the person calling for help from the burning car, but Hildy and Frank shrug it off with callous indifference, with Hildy scolding Belinda for being such a downer about the whole thing, telling her “you’re driving me nuts!” (8) and “You better get your act together. You’re getting to be a real bore with all this” (11). Belinda keeps one eye on the news, waiting for a story about the accident, or for the police to show up at her house when she and her friends are identified by the mysterious figure she saw that night. And she doesn’t have to wait long: when she gets home from school one day, the cops are there waiting for her, saying someone had called and said she’d had an accident; while they’re initially concerned for her welfare, they quickly become annoyed at the seeming prank. She gets a mysterious package on her front stoop with a calendar page for the month of April, with the 1st circled in dried blood, and a couple of days later, she opens her mailbox to find a mutilated doll’s head covered with putrefying entrails. Somebody lurks outside her bedroom window in the middle of the night and calls her a murderer. It sure seems like someone knows what they did and wants to make them pay, but even then, Hildy and Frank keep telling Belinda that she’s overreacting and they’re not in any danger.

Belinda’s parents are divorced and her mom works double shifts at the hospital, which means Belinda’s home alone a lot of the time. She also works as a tutor to help make some extra money— and things get even weirder when Belinda is hired to tutor a young man named Adam Thorne, who has recently been in a bad accident and is unable to go to school. His accident was just weeks earlier and he’s not one of their classmates: he goes to a school a couple of hours away and his mother sent him to stay with his father and stepmother while he recovers. The timing, the location, and the severity of his injuries—which include stitches on his face and injuries to his legs that have left him reliant on a cane to get around—seem too close to her own accident to be coincidence. But she takes the job to see if she can learn more about him. She feels guilty, and her sense of duty is exacerbated when she finds out Adam has a cold and complicated home life: his father is in a coma and dying as a result of injuries he sustained in the accident and Adam’s stepmother hates him. He has a step brother named Noel who he barely has a relationship with, his mother has sent him away because she doesn’t know how to deal with him, and he’s angry at everyone all the time, getting pleasure out of intimidating and scaring the people who try to get close to him, including Belinda. Belinda’s guilt—and her fear that Adam’s current condition is her fault—keeps her coming back to the house, however, putting up with his antics and abuse as she tries to find out the truth, showing him compassion that he isn’t getting from anyone else in his life, and hoping to assuage her own guilty conscience.

The house is lavish, complete with a butler named Cobbs, who has an incredibly dry sense of humor and a kind heart, as he makes Belinda tea and tries to encourage her not to take Adam’s behavior personally. After her first unsettling interaction with Adam, Cobbs invites Belinda to “Sit down, miss. I’ll fix you some tea and toast, and then I’ll take you home. If you’ll forgive my saying so, you look a trifle … anxious” (44). He is caring and solicitous but also a bit snarky and when Belinda is unsure about whether she’d like milk in her tea, there’s a quiet moment in which “Cobbs lowered his head, but Belinda could almost swear he’d rolled his eyes,” before he chides her that “It’s the civilized thing to do, miss” (45). This understated forthrightness extends to his interactions with everyone in the household, including Mrs. Thorne, responding to her uncertainty about what to wear with a deadpan delivery suggestion of “What about a gag, madame?” (60), which she either mishears or chooses to ignore, responding with “What about my bag? How should I know where the bags are, Cobbs? That’s your job!” (60, emphasis original). Cobbs keeps just under the radar, letting off his low-key zingers, but always aware of what’s going on in the house and looking out for Belinda’s safety.

Adam’s father loves snakes, and there are glass boxes with a wide variety of snakes all over the house. Adam’s stepmother leaves on a business trip but then ends up inexplicably going missing, and Cobbs makes frequent calls and visits to the hospital to monitor Mr. Thorne’s condition, though it really seems like everyone else in the family is just waiting around and wishing he would die already. Other than Cobbs’ kindness, the only real perk of the job is Adam’s step brother Noel, who is cute, funny, and takes an almost immediate liking to Belinda, getting into the habit of driving her home from her visits to see Adam and even taking her on a date to her senior class picnic.

In the meantime, Belinda’s relationship with Hildy and Frank can only be described as increasingly complicated. They still don’t get why Belinda can’t just forget about the accident already, and when her obsession only deepens once she starts working with Adam, they remain aggressively dismissive of her concerns, unwilling to take any responsibility for what happened. When Belinda pushes the issue, Frank tells her that if they end up getting in trouble, he and Hildy will both tell the police that Belinda was the one who was driving. Belinda is further horrified when she finds out that some of the threatening and terrifying things that happened in the aftermath of the accident—including the police showing up because of an anonymous accident tip and the creepy calendar page—were another one of Frank’s sick jokes, intended to torment Belinda. After that, it’s almost impossible to figure out what’s a “joke” and what might be a legitimate threat. The only thing that’s certain is that Belinda needs better friends.

She can’t trust her friends but she also can’t trust her new boyfriend. While Belinda has been worried about Adam knowing what she did and wanting revenge, it never occurred to her that Adam and Noel might be in it together or that the accident was a staged scheme to kill their parents and gain their inheritance. There was an accident and it was the same accident that Belinda and her friends contributed to, but Adam’s accident was an elaborate plot, with Adam intentionally jumping from the car and sending it hurtling down the embankment with his father and stepmother inside. But because of the dangerous back-and-forth between the two cars, it wasn’t going fast enough to kill Mr. and Mrs. Thorne outright—which was the original plan—and Adam’s escape timing was off, resulting in him being badly injured as he leapt from the car.

Adam’s whole “jump from a moving car while committing murder” thing pretty fine tuned, because he did the same thing when he was ten years old and caused the accident that killed his aunt and uncle, who he’d been sent to stay with for a while. Adam has always been difficult and confrontational, with Cobbs describing young Adam as “troubled” (152). When he was sent away to stay with his aunt and uncle, Adam begged to be allowed to come home and even tried to run away. The truth of what happened during that time with his extended family is shrouded in mystery. As Cobbs tells Belinda, Adam “claimed they were unkind to him … that they … abused him … They, on the other hand, insisted that he was deliberately argumentative and disobedient. They claimed he threatened them, and they wanted to send him home straightaway” (152). But Adam’s parents won’t take him back, preoccupied with their increasingly vicious divorce proceedings. Shortly after this, Adam’s aunt and uncle had an accident that eerily mirrors the one Belinda and her friends witnessed, with their car driving off the road, down an embankment, and catching fire. Adam is “thrown clear” (152) of the car and while he is badly injured, he survives, which is more than can be said for his uncle, who died instantly, and his aunt, who uses her dying breath to tell the doctors that Adam grabbed the steering wheel and intentionally caused the crash (153). This revelation raises even more questions thant it answers, as Belinda tries to figure out Adam’s motivations, the trauma response that must have been triggered by the second accident, and whether he’s a murderous psychopath or just an incredibly unlucky and misunderstood boy.

When the truth comes to light, it’s a combination of Belinda’s suspicions and dangers she never anticipated: Noel seduces Belinda and earns her trust, then leaves her alone at the Thorne house so that Adam can kill her to make sure she keeps their secret. He also kidnaps Frank and Hildy for good measure—who honestly kind of deserve it—and when Adam doesn’t murder Belinda fast enough, the two boys put Frank, Hildy, and Belinda in a car and prepare to push them over a cliff, following in the tire-tracks of Noel’s mother, who never really left for her business trip at all.

Cobbs may be a man of few words, but he’s incredibly observant and his attention to detail brings the police on the run and saves Belinda and the others (though Belinda continues to stubbornly cling to the belief that Noel wouldn’t really have killed her). In an odd twist, in the book’s conclusion, Cobbs shows up at Belinda’s house, offering his services as a live-in butler to Belinda and her mother, judging the state of the house and their family more generally, with “his eyes raised in secret appall at the messy kitchen” (214) and his pointed suggestion that “It appears to me that Miss Belinda needs a stronger hand … Perhaps then she would find herself in far less trouble … and make a wiser choice about her men” (215, emphasis original). This is an odd exchange and further compounded by the fact that after being well taken care of in Mr. Thorne’s will, Cobbs wants to work for Belinda and her mother for free, because he finds himself with “an abundance of leisure time and no way of filling it” (215). In addition to continuing his long career of domestic service with Belinda and her mother, he does seem to genuinely care for Belinda, though he would never come right out and say so. When she finds out that he was watching out for her the whole time and making sure nothing bad happened to her, Belinda is overwhelmed and grateful, though Cobbs responds by saying “Hmph. There’s absolutely no need for sentimentality, you know. I was merely doing my duty, nothing more, nothing less” (216, emphasis original). His reserve breaks down just a bit when Belinda starts crying and he comforts her, and when she tells Cobbs that she loves him, he responds with “And I you, miss” (218, emphasis original), which is as close as Cobbs gets to emotional displays. Still, his motivation for wanting to go from working in a mansion for a wealthy family to looking after a lower-middle class mother and daughter for free is a bit of a curve ball. Maybe he’s just incredibly kindhearted, maybe after a life spent in service to the Thorne family he doesn’t know who he is without someone to serve and has latched on to Belinda as that replacement, or maybe he’s up to something nefarious. It’s an inexplicable ending and an unsolvable mystery.

But perhaps the most confounding thing about April Fools is that while Belinda and her friends think they may have committed manslaughter, their consciences are cleared and they become victims rather than villains when they find out the people they thought they killed were actually trying to kill each other. But really, does that make it any better? Does it make Belinda and her friends less culpable? They were still driving irresponsibly, they still hit another car and nearly forced it off the road. They still contributed to an accident and fled the scene without doing anything to help the people who were trapped in the car. Realizing that they were part of a much larger plot doesn’t invalidate the terrible choices they made. They are both victims and villains, the pranksters and the ones being pranked. Frank may have claimed the title “King of Fools,” but they all share the crown.